by Samir Raafat

The Egyptian Mail, December 3, 1994

Reproduced in The Khedivial Post published by Max Group, Cairo, 1995

|

|

|

|

|

|

EGY.COM - HISTORICA

|

|

by Samir Raafat

The Egyptian Mail, December 3, 1994

Reproduced in The Khedivial Post published by Max Group, Cairo, 1995

A SIMULTANEOUS need for a courier service was created with the invention of transportable writing materials. In Egypt, where writing had become an institution, Pharaoh's missives had to reach the outer provinces faster and more efficiently. And with the subsequent discovery of papyrus, the development of a postal system was a matter of time.

Ptolemaic Egypt initiated the equivalent of the "express" and "regular" postal service; the former being the exclusive use of the ruler's court. The courier from Fayoum took all of four days to reach Alexandria. And during Egypt's Roman and Byzantine era, horse relay stations replaced Nile waterways. The postal system was christened "cursus publicus". Under the Arab caliphate of Muawia (d. 679), Egypt organized its first formal postal system and called it "al-Baryd" with designated routes starting (or ending) at the Cairo Citadel, then the formal seat of Islamic Egypt. In the 12th century, a regular airmail service was introduced for the first time. The "pigeon express" traveled north as far as the Euphrates valley. Its southern route reached the Red Sea port of Aidab in Nubia. The governor's pigeons were marked with a special seal either on their beaks or on their claws. This revolutionary service came to an end when the Tartar invaders purposefully destroyed the pigeon relay systems in their attempt to disrupt a communication system so important to the survival of the endangered empire.

The modern postal system as we know it today was developed by Viceroy Mohammed Ali Pasha (r. 1805-48). The service was primarily for the use of the state enabling the central government to remain informed of daily developments all across the pasha's expanding realm. Written messages from Alexandria reached Cairo within 24 hours, and it took 50 days for an identical missive to reach Khartoum which Mohammed Ali had conquered in 1821. The chief of the postal couriers at the time was Sheik Omar al-Hammad. He was was succeeded by Sheik Hassan al-Badihi. It was also during this time that the telegraph was introduced with tall equidistant and intervisible relay towers erected in a straight line between Cairo and Alexandria.

During the viceroy's reign a 2-7 millimes tax was levied on a one dirham (3.12 grams) letter sent by a private individual from Cairo to Middle Egypt. For the same letter to reach Upper Egypt, the cost rose to 1-3 piasters, a hefty amount in those days. Correspondence to and from Europe was effected with the cooperation of ship captains and foreign consuls. It was not until 1831 when the first branches of various European postal services surfaced in the ports of Alexandria, Port Said and Suez.

The first foreign power to exercise its privilege under the Ottoman regime of Capitulation's (a form of extraterritoriality for foreign residents conducting business within the Ottoman Empire) was Great Britain which opened post office branches in Alexandria and Suez. These were then closed in 1878. France opened its own postal service in Alexandria at 4 Blvd. Ramleh, and years later, another one was installed in Port Said. Both remained in operation up to 1931, long after the other foreign post offices (Austria 1838-89; Greece 1859-82; Italy 1866-84; Russia 1867-75) had ceased to exist.

For the transport of their mail, foreign post offices operating in Egypt used their own national stamps and their own carriers. For instance, Austria, then at the center of a large empire reaching Trieste on the Mediterranean, owned one of the most important merchant fleets of the day. This included the famous LLoyd Trieste Line.

Craving to become part of Europe's age of enlightenment, Mohammed Ali's descendants, namely Said (r. 1854-63) and Ismail (r. 1863-79), opened Egypt's shores to thousands of economic migrants from Europe and the Ottoman Empire. Quick to capitalise on a situation where Egypt was on the threshold of an unprecedented economic boom, a contingent of Livornese Jews headed by Carlo Meratti (d. 1843) launched a private courier service between Egypt and Europe, and later within Egypt itself. The need for such a service was evident as the numbers of new arrivals swelled, be they entrepreneurs, canal builders, surveyors or house servants from the poorer provinces of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The impending inauguration of the Suez Canal in 1869 proved Meratti right. Soon after, Egypt became the region's principal commercial and maritime hub.

Carlo Meratti's private courier operated under the protection of the Duchy of Tuscany and therefore exempt from sovereign Egyptian Law. As he expanded his service Meratti installed his postal system's head office at Place des Consuls, Alexandria's main square. When he passed away the company was taken over by Meratti's heirs, Cleo and Tito Chini (d.1864), and the latter's associate Giacomo Muzzi from Bologna.

Despite their valuable contributions to Egypt's modern postal service, Meratti and Chini are not as historically connected with the development of Egypt's first private service ÷ the Posta Europea ÷ as was their countryman Giacomo Muzzi. A short description of the Chini brothers' role is mentioned in Baron Samuel Selig Kusel's book An Englishman's Recollection of Egypt, written in 1915. Kusel was married to Tito Chini's sister, Elvira.

Posta Europea opened branches in the prosperous towns of the Delta and Upper Egypt. In 1854, when it realized it was no longer able to compete, the government-run postal service graciously gave way to its private sector rival. That year also saw the opening of Egypt's first railway link between Cairo and Alexandria. Posta Europea wasted no time in concluding a profitable arrangement with the Egyptian Transit Authority for the exclusive transport of its mail. Signing on behalf of the Authority was Egypt's future prime minister, the Armenian Nubar Nubarian Pasha. Similar concessions were denied to the other private postal services for an initial five year period.

In return for its exclusivity, Posta Europea opened several branches along the railway's route. On March 5, 1862, Premier Cherif Pasha, acting on behalf of Viceroy Mohammed Said, awarded the Muzzi-Chini venture a 10-year franchise for the free transport of Posta Europea's mailbags on the Egyptian State Railway. Posta Europea also undertook the distribution and delivery of all government correspondence. That year, the Egyptian government postal service all but ceased to exist.

Tito Chini died in 1864, the year after Viceroy Ismail ascended Egypt's throne. Realizing the Postal Administration was an important cog in the state wheel, the new viceroy (elevated to khedive in 1867) instructed his French bankers to negotiate the acquisition of Posta Europea at whatever cost. On January 2, 1865, Charles Vernone, representing Edouard Dervieu & Cie., paid Giacomo Muzzi and Tito Chini's numerous heirs, the sum of 950,000 francs in return for their company. A generous man, Ismail conferred on Muzzi the honorary title of Bey and the first directorship of the new Poste Egyptienne.

At its inception, the new state-owned postal company operated under the aegis of Minister of Public Works, Nubar Pasha, with whom Muzzi shared several common interests, one of them being their pronounced antipathy for the French; a feeling which was by and large part reciprocated by successive French consul-generals. Perhaps this was because Italian, instead of French, was the language used by the postal authority.

During its early years the new government organization changed venues several times. At first it was accountable to the Bureau of General Finances. In 1867, it somehow became the responsibility of the prime minister; then that of the ministries of justice in 1875; agriculture 1876; and finances again in 1878. On June 2, 1919, Sultan Fouad (afterwards king from 1922 until he died in 1936) decreed that henceforth the Poste Egyptienne would be the responsibility of the newly created ministry of communications under Ziwar Pasha. Ziwar was responsible also for both the Egyptian State Railway, Telegraph and Telephone (ESRT&T) Administration as well as the Ports and Lighthouse Authority.

Barely three years after the takeover of the Posta Europea, Khedive Ismail state postal system faced an unexpected challenge. In April 1868, the Compagnie Universelle du Canal Maritime de Suez, whose waterway had yet to be formally inaugurated, started issuing its own stamps for use within the Canal Zone. Here was yet another form of blatant abuse under the Capitulations system. The irritated khedive protested and the service was discontinued in October of the same year, not because the Compagnie ran scared but simply because Monsieur de Lesseps did not want to provoke unnecessarily the fury of his benefactor. The discontinued stamps are today among the rarest in international philately.

When Ismail purchased the Posta Europea it had 19 offices and branches in Egypt. As railways expanded, new postal branches were added. By year-end 1865, the Poste Egyptienne operated 28 branches. That same year, with the blessings of the Sublime Porte (Ottoman government), a branch of the Poste Egyptienne opened in Istanbul. This development coincided both, the re-organization of the maritime service between Egypt and Turkey, and with the addition of eight Egyptian-owned merchant ships under contract to the Medjidieh Co which operated the Alexandria-Piraeus-Levant-Istanbul route. The following year, the Poste Egyptienne established branches in Smyrna (Izmir), Jeddah, and in 1870, opened new ones in Gallipoli, Beirut, Cavalla, Salonika, Tripoli and Rhodes. South of Aswan, the Poste opened branches in Souakin, Massawa, Khartoum and Kassala in 1867, 1869, 1873 and 1875 respectively. In 1877, thanks to Muzzi's countryman Licurgo Santoni, eight more branches were opened in the Sudan.

The Poste Egyptienne had become an icon in the Ottoman Empire's communication network.

During the reign of Khedive Mohammed Tewfik (r. 1879-82), the Egyptian and Turkish governments agreed on July 11, 1881, that all activities and assets of the Poste Egyptienne throughout the Ottoman Empire excluding Egypt and the Sudan would be transfered to the re-organized Turkish Postal Administration. At about the same time, the Poste Egyptienne underwent several internal changes of its own. Its main branches including the head office in Alexandria, were subdivided into different categories. Category No.1 carried out all or part of the traditional postal activities such as ordinary and registered mail, parcel post, savings and international money orders. Category No.3 was limited to acceptance and delivery of ordinary and registered mail. Category No.2 was somewhere in between. Village post offices were in Category No.3 and depended to a large extent on the village omda or chief. Because rural Egypt had no streets per se, and the very few that existed were unnamed and the houses unnumbered, it was for the recipient to check with the post office if he had received mail.

From an item in The Egyptian Gazette of January 10, 1908, we note that Cairo's central post office was near Attaba al-Khadra Square just across from the Caisse de La Dette Publique's offices on Bedak Street which ran between Blvd. Abdel Aziz and Teatro al-Fransawi Streets. The Central Post Office was divided into alphabetical sections A-D; E-L; L-P; R-Z. From the disgruntled author of the same article we note that: "The Post Office building is utterly unworthy of such a city as Cairo." The writer goes on to suggest that "the letters might be divided into a few more sections or each section might have an extra clerk and pigeon hole." Later on, the writer pays a few compliments, "I must, however, pay tribute to the courtesy shown me by Mr. Williams, the director at Cairo and his chief, Borton Bey over some letters that were missing through no fault of the post office. I regard the administration of the Egyptian post office as marvelously well run, considering the exceptional difficulties of the diverse languages and the continual arrival of mails by every steamer and the impossibility of obtaining the national staff that France, England and Italy can obtain. Yours, Norman Hamilton."

As Cairo expanded so did the postal administration. A new Parcel Post and Postal Customs Building was opened in July 1912, next to the old headquarters. An additional service introduced in the new building was the ladies parcel's counter "which has been set apart for the fair sex of every nationality in order to prevent them from being crowded by servants." Norman Hamilton's letter to the Gazette mentions two senior executives working for this growing "Egyptian" administration.

According to the Poste Egyptienne's 1913 roster, we note that the executive posts of secretary general, chief inspector, chief accountant and chief of administration were occupied respectively by Ariel Goldstein Bey, Salib Claudius Bey, Claude Barton and Michel Charbin. Where then were the Egyptians?

The Poste Egyptienne's postmaster general between 1907-24 was the Englishman Nevile Travers Borton Pasha (1870-1938) a one-time governor of the Red Sea and director of Egyptian Customs. Borton was assisted by another favorite of Lord Kitchener, the one-eyed Egyptian-born and self-taught linguist Arthur Owen Williams Bey who became Cairo's veteran postmaster. Williams was assisted by a Levantine Jew called Naoum Effendi. Even before Borton became postmaster general, and long after Muzzi Bey's departure in 1876, this important post was occupied successively by khawagas (foreigners). These were: A. Caillard Pasha from 1876 to 1879; the Englishman W.F. Halton Pasha up to January 1887; by the Syrian Sir Joseph Saba Pasha, (b.1852) for the net twenty years. Saba was a knight commander of the Order of St. Michael and St. George. He had joined the post office in 1872 as a clerk which made him the postal administration's longest serving executive. He represented Egypt three times at Postal Union congresses once one had been created in Berne, Switzerland in 1874. After retiring in 1907, Saba Pasha was appointed minister of finance on February 23, 1910. In recognition of his services an entire garden district was named after him in his native Alexandria.

It was only after the retirement of Borton Pasha that the top position was awarded to an Egyptian. Hassan Mazloum Pasha remained in charge until he hastily resigned in 1929. His decision to leave was not because the pasha craved an ambassadorship in Europe or a cabinet portfolio, but because he was about to join the expanding class of Egyptian financiers with a directorship in almost every blue chip company board existing at the time. Like Joseph Saba Pasha, Mazloum Pasha was a native of Alexandria with an entire district in that city's Ramleh district named after his family (near Saba Pasha station). Years later, between 1946-54, Mazloum Pasha presided over another famous garden suburb. As chairman of the Delta Land & Investment Company, Mazloum Pasha was for some time responsible for the suburb of Maadi.

The year Mazloum Pasha resigned from the Poste Egyptienne ushered in the first airmail postal service between Alexandria and London via Genoa. Alexandria remained Egypt's principal commercial gateway until June 1931. But with the arrival of air travel and the subsequent decline of maritime communication, the Poste Egyptienne moved its headquarters from Alexandria to Cairo. Mohammed Charara Bey was the new director. The Attaba headquarters was enlarged and an additional floor added. That same year the last foreign post office operating in Egypt closed its doors. By year-end the Poste Egyptienne had 4,566 branches spread all over the territory with a ratio of one outlet for every 3,350 inhabitants (Egypt's entire pop 15.3 million). The Poste Egyptienne disbursed an aggregate annual salary of L.E. 460,538.

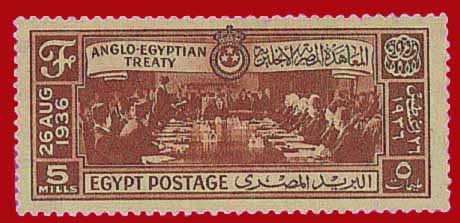

February 1934 marked the peak of Egypt's postal history when Cairo played host to the 10th Universal Postal Congress. Its president was Egypt's minister of communication, Ibrahim Fahmi Karim Pasha. To mark the occasion, two commemorative stamps bearing the portrait of Khedive Ismail were issued in tribute to the man who introduced the first modern postal administration in Egypt, and under whose reign the first Egyptian stamp was issued in 1866.

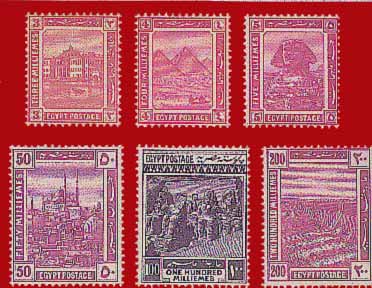

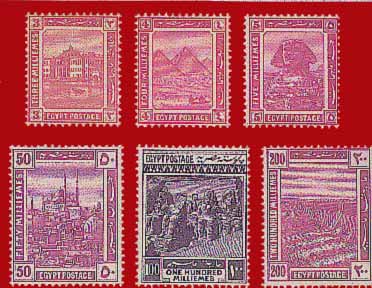

The commemorative stamp issue of 1934 was the 12th in a special series launched in 1925 on the occasion of the convening of the International Geographical Congress in Cairo. The first three emissions of Egyptian stamps were lithographed respectively in Genoa (1866), at Alexandria's Penasson Printshop (1867) and at the National Printshop of Boulac, Cairo (1872). When Khedive Tewfik ascended the throne in 1879, the printing of Egypt's stamps was taken over by Messrs. de la Rue & Co. of London and the method of production was changed to the "surface printing" technique. In 1919, the contract was taken over by Harrisons & Sons who introduced the "multiple star and crescent" watermark. In 1925, during Mazloum Pasha's administration, Egypt's stamp production was brought home and put under the able direction of the Survey Department in Giza.

The "Egyptienne" in the postal administration's name had become authentic at last.

Reader Comments

Subject: Fw: Postmaster at Alexandria

Date: Sun, 20 Aug 2000 14:04:30 -0700

From:"Irv Mortenson" <irvmort@olypen.com>

I found your facinating article on the Web and thought I'd write and inquire if you might be able to assist me in researching Henry Augustus Harrington, who worked with the Egyptian postal services from 1886 till 1916 or later. See the forwarded message below for details on Harrington's service and his medallic rewards for that service. I'd be most interested in any details of the man's life and career while in Egypt. You had some details on the khawaga postmaster of Cairo during much of that period - Arthur Owen Williams Bey. I hope that there are records for Harrington as well.

Thanks for your consideration -

Irv Mortenson

133 San Juan Avenue

Sequim, WA 98382

USA

irvmort@olypen.com

fax: 360-683-3343

I am writing in hopes that your archives might contain information on Henry Augustus HARRINGTON, whose medals I have in my collection and whose career | (both army and civil) I'm researching. HARRINGTON'S medals include:

Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, MBE, 1st Type (Civil), to:

Unnamed as Issued

Egypt Medal (1882 date), clasps: Tel-El-Kebir / The Nile 1884-85, to:

2288. LCE CPL H. HARRINGTON. 3/K.R.RIF:C

Order of the Mejidie, 5th Class Breast Badge, to: Unnamed as Issued

Order of the Nile, Officer’s Breast Badge, to: Unnamed as Issued

Khedive’s Star (1882 date), to: Unnamed as Order of the Nile - The London Gazette of 29 December 1916 -

p. 12656

MBE - Third Supplement to The London Gazette of 30 March 1920 -

p. 3835 Served: 3rd KRRC As Director of Posts at Alexandria, Egypt

Briefly, here is what I know of his work with the Egyptian Postal Service1883 to 1916:

Postal Arrangements in Sudan in 1884:

The trained staff available for postal service consisted of the Chevalier Santoni, nine Egyptian employees, and three or four British non-commissioned officers [one of whom was Sergeant Harrington] who had worked at the Post Office at Cairo. These men were reserved for the three principal Post Offices [Sergeant Harrington was to serve with on the staff at Dongola as Postmaster during the 1884-1885 Sudan Campaign], the intermediate offices being served for the most part by convalescent soldiers.

Mails were made up at Cairo for battalions and corps on information telegraphed to the Commandant of the base. A parcels post was established under the superintendence of the Commandant of the base. The mails were carried from Cairo to Assiut by railway; Assiut to Assuan by steamers; Assuan to Philae by railway; Philae to Halfa by steamers; Halfa to Sarras railway, Sarras to Abu Fatmeh by camel; and Abu Fatmeh to the south by| camel.

Separate contracts were made for the carriage of letters, parcels, and

newspapers, by camel; three camels sufficed as a rule for the letters, and ten for the parcels, &c. Local posts were also organized by the military

authorities on the Line of Communications; the means of transport being

almost entirely camels, sometimes hired, but generally government property.

The post riders were either natives or Egyptian soldiers.

Regular post offices were opened at Dongola [where Harrington was appointed postmaster] and Korti and also a transit office on board the Lotus, by the Egyptian postal authorities; in which a complete postal service was established, letters could be registered and money orders obtained. (History of the Sudan Campaign - Vol. 1 - p. 86)

01.11.1885 Harrington reverted to Regimental Duty, from pay with the 2nd Essex Regiment at Assuan.

01.01.1886 Sergeant H.A. Harrington purchased his discharge in Egypt to

accept an offer by Egyptian authorities for a position in the Post Office.

29.12.1916 The London Gazette (page 12655) announced that: The KING has been pleased to give and grant unto the undermentioned gentlemen His Majesty’s Royal licence and authority to wear Decorations as stated against their respective names) which have been conferred upon them by his Highness the Sultan of Egypt in recognition of valuable services rendered by them: Fourth Call of the Order of the Nile. (page 12656) Henry Harrington, Esq., Director, Post Office, Alexandria

30.03.1920 The Third Supplement to The London Gazette, dated 26 March, 920, (page 3757) noted that: The KING has been graciously pleased to give orders for the following promotions in, and appointments to, The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire for services in connection with the War, to be dated 1st January 1920:-

To be Members of the Civil Division of the said Most Excellent Order: (on page 3835) Henry Augustus Harrington, Esq., Postmaster, Alexandria

|

xx.xx.1921 Burke’s Handbook to the Most Excellent Order of the British Rmpire for 1921 reads on page 242:

HARRINGTON, Henry Augustus, M.B.E., b. 10 July, 1864; s. of the late John William Harring. Educ.: Army Schools, Local Director of Ports [sic - posts] Alexandria, Egypt. War Work: Canteen work, and general interest in the morale welfare of the troops (British) quartered in Alexandria during the War. Addresses: The Overseas Club, General Buildings, Aldwych, London, W.C.; Post Office, Alexandria, Egypt. (M8370)

|

|

|

|